A nearby galaxy merger harbors two monster black holes that appear to be the closest pair ever detected in multiple wavelengths, according to a new study.

The two galaxies, collectively known as UGC 4211, are located just 500 million light-years from Earth in the constellation Cancer and are in the end stages of merging. Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), an international observatory in Chile, scientists discovered the two black holes feasting on the byproducts of the galactic merger, the research team said in a statement (opens in new tab).

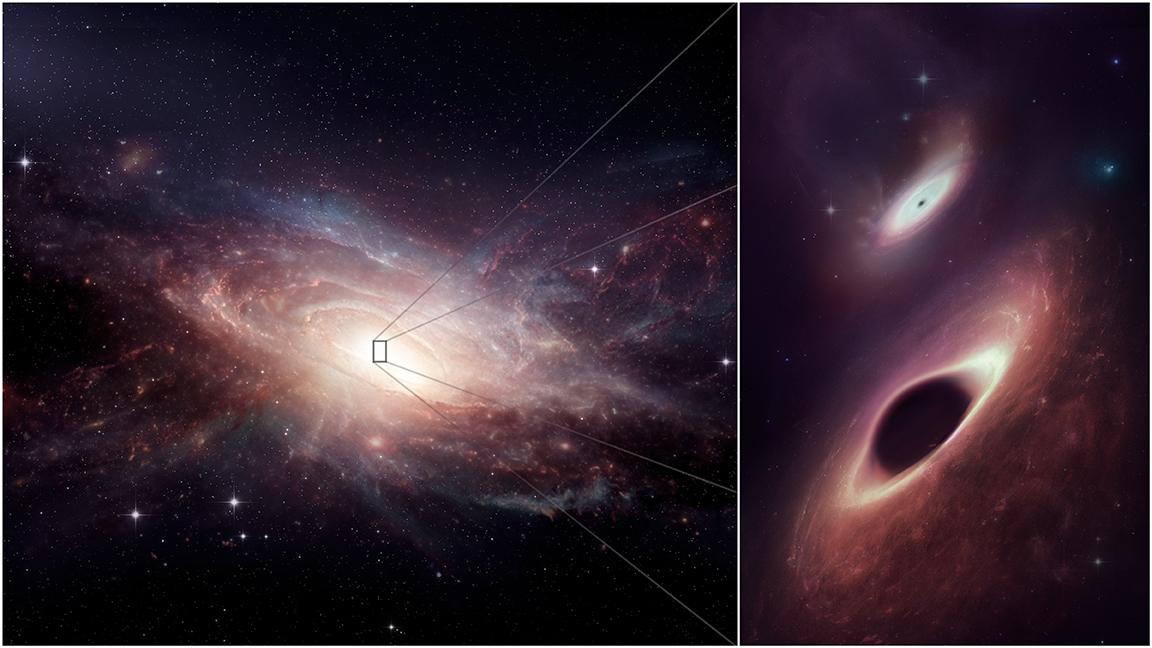

As these supermassive black holes devour nearby matter, they emit bright jets and winds, creating a highly luminous active galactic nucleus that is detectable by ALMA. The recent observations suggest that the two black holes are only 750 light-years apart.

Related: Supermassive black hole pair nearest Earth is locked in a violent cosmic dance

An artist’s depiction of the late stages of a galaxy merger, with two central black holes particularly close together. (Image credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO); M. Weiss (NRAO/AUI/NSF))

“ALMA is unique in that it can see through large columns of gas and dust and achieve very high spatial resolution to see things very close together,” Michael Koss, lead author of the study and a senior research scientist at Eureka Scientific, said in the statement. “Our study has identified one of the closest pairs of black holes in a galaxy merger, and because we know that galaxy mergers are much more common in the distant universe, these black hole binaries too may be much more common than previously thought.”

Although common, galactic mergers in the distant universe can be difficult to observe. Therefore, detecting a nearby galaxy merger like UGC 4211 with an active pair of supermassive black holes could aid in the detection of gravitational waves produced by these cataclysmic events.

“There might be many pairs of growing supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxies that we have not been able to identify so far,” Ezequiel Treister, co-author of the study and an astronomer at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, said in the statement. “If this is the case, in the near future we will be observing frequent gravitational wave events caused by the mergers of these objects across the universe.”

To get a full picture of UGC 4211, the researchers used data from other telescopes, including the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the Hubble Space Telescope, the Very Large Telescope and the W. M. Keck Observatory. Together, the data offered a view of the galactic merger from multiple wavelengths.

“Each wavelength tells a different part of the story,” Treister said in the statement. “While ground-based optical imaging showed us the whole merging galaxy, Hubble showed us the nuclear regions at high resolutions. X-ray observations revealed that there was at least one active galactic nucleus in the system. And ALMA showed us the exact location of these two growing, hungry supermassive black holes.

“All of these data together have given us a clearer picture of how galaxies such as our own turned out to be the way they are, and what they will become in the future,” he added.

Our Milky Way galaxy is on a collision course with another spiral galaxy called Andromeda. The collision is still in its early stages and is predicted to occur in about 4.5 billion years.

“What we’ve just studied is a source in the very final stage of collision, so what we’re seeing presages that [Milky Way-Andromeda] merger and also gives us insight into the connection between black holes merging and growing and eventually producing gravitational waves,” Koss said in the statement.

Their findings were published Monday (Jan. 9) in The Astrophysical Journal Letters (opens in new tab); the researchers also presented the work at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society, being held this week in Seattle and virtually.